There’s a Stop the Steal flag flying outside my great-grandmother’s childhood home.

We’d only pulled off Interstate 80 at Grand Island, Nebraska to hit the playground, grab some dinner, and make the pilgrimmage. It’d been awhile. On our last visit in 2016, we’d cruised by the old white house at 610 W. Division so I could prove my Great Plains bonfides to my South Dakota-born, Iowa-raised bride. Jenny enjoys a good ritual as much as I do; we laid our infant son under a tree in the front yard, got the pic, then hit the road.

Now, eight summers later, there was a only twisted stump. The housepaint was flaking hard, and trees of heaven were making a move on the front hedge. Just off the front porch rose a flagpole I didn’t remember, the serious kind with a metal ball on top. From it hung the good ol’ Stars and Stripes, upside down.

We gasped. The so-called ‘Stop the Steal’ symbol is a gut punch, by design—none of the photo-shop muck of most Trump gear, and uncannily easy to read even without a breeze. We nixed the kids-in-the-yard shot and nervously circled the block. I pulled up across the side street and left the car running. I wasn’t leaving without a photo. Were they home? The blinds were pulled. Dude’s gotta have a gun. I hopped out and took a picture, then we sped off in search of dinner. Three days later we flew home to New Zealand.

Now the easy move here would just be to declare You Can’t Go Home Again and get on with my rootless expat life. When our energy flagged on the long Nebraska drive we revved up on a playlist of ’90s country mamas: Jo Dee Messina’s got her rear view mirror torn off, so why shouldn’t we?

But these are strange days for us leavers. Just a few days before we hit Grand Island, Kamala Harris picked Tim Walz for her veep. Suddenly my dear party of metropole-bound strivers is ecstatic to have a football coach they can genuinely sell as The Guy Who Didn’t Leave. Walz is small-town Nebraska born (Butte, dwindled now to pop. 286) and raised (Valentine, pop. 2,633) who stuck around for college at tiny Chadron State, one of the most geographically remote universities in the lower 48. Jenny and I were out there for the 2017 eclipse. Nice town. The Sandhills are a wild inland sea of rolling earth, utterly treeless but green enough in high summer; come sunset they glow with a high and lonesome beauty I can hardly bear to contemplate. We sat in the one college-professor bar and eavesdropped and wondered, unseriously, what it would be like to teach there. Then we cool kids flew back to Shanghai.

I mean, it’d be hard to make it stick out there. Even Walz eventually left for Minnesota, which until I married Jenny I never realized was the Plains’ own power center, considerably bigger and richer than the big squares west and south. Like some pale echo of Walz, though, I have clung to this idea of Nebraska as an ancestral home.

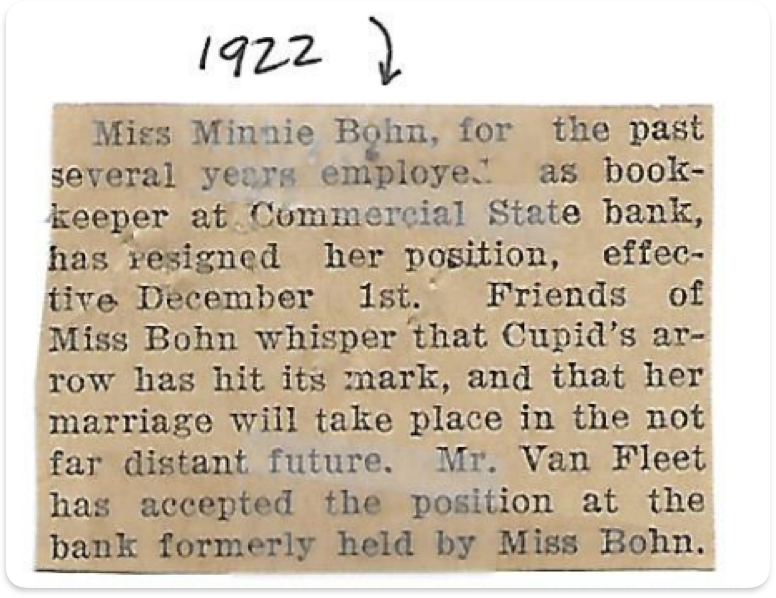

Butte and Valentine are up on the northern border; Grand Island, founded by German Settlers in 1857, is a much bigger town (pop. 53,000) a few hours south, named for a long sandbar in the Platte River. In the late 1880s my great-great-grandfather Henry Bohn—German surname, like Walz—moved out from western New York state to join his brother’s new wholesale grocery business. He soon brought his bride, Minnie Grant, to join him, and my great-grandmother Minnie Bohn was born in 1890. She was baptized at St. Stephen’s Episcopal, a red gothic hulk of Colorado sandstone still going strong today. As a young babysitter, the story goes, Minnie changed the diapers of an infant Henry Fonda, whose own family lived briefly down at 622 W. Division. As a young woman Minnie took a job at a bank in town, then eventually quit to marry the railroad man Ray McCaulley. The newlyweds bought a house a few blocks away—also still standing—and my grandmother Mary was born in 1923, her brother the year after. Penzoil hired Ray away from the railroad, then in 1938 promoted him to the California office. Teenage Mary drops Nebraska like a hot rock and graduates from Hollywood High with dreams of being a painter. Call it a biblical forty years in the Great American Desert, smack in the middle of a three-generation run from NY to LA. Bog-standard American story, that one. That famous (and apocryphal) Horace Greeley line: “Go West, young man, and grow up with the country.”

But is the heritage Nebraska, or the movement through it? There were visits, but neither Minnie or Mary felt a strong call to return. My own mother, Mary’s daughter, remembers one childhood trip, and then nothing until they brought Minnie home to be buried at St. Stephen’s in 1981. Henry Fonda never went back either; the Hollywood legend is perhaps best known today for playing iconic Plains-deserter Tom Joad in The Grapes of Wrath (1940).

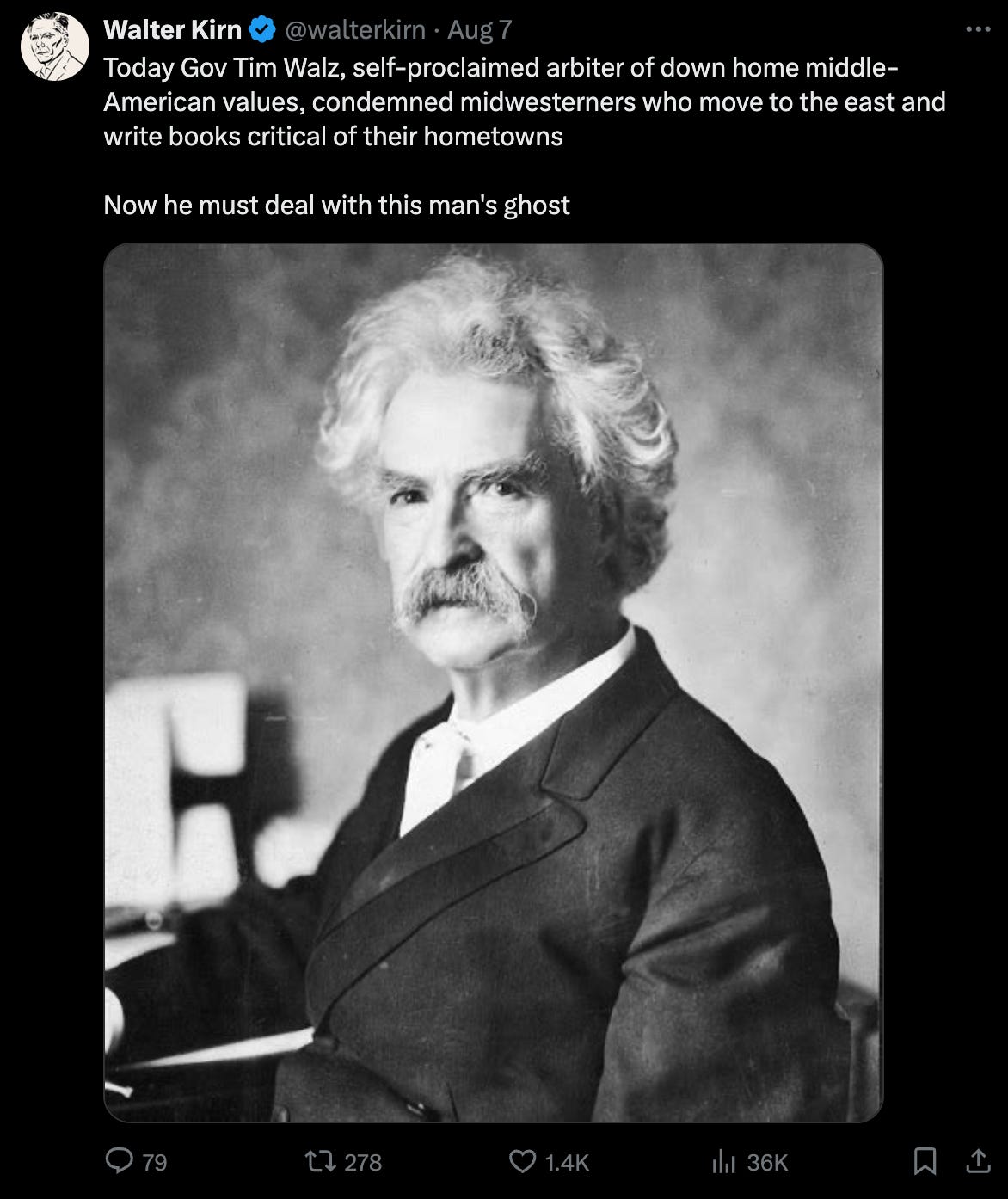

What’s wild about Walz’s rollout, then, is the speed with which the Dems have tossed this age-old American story of movement aside for a new geographic populism. Right from jump, the new attack line against his Republican counterpart J. D. Vance was that Vance had the temerity to jump from Ohio to Yale, trading on stories of home all the way up. You can find the man an arrogant creep and still note that his path to success, at least for a certain subset of mostly white, middle-class dreamers, is a foundational tenant of our once-proud meritocratic faith. Clinton from Arkansas to Oxford. Obama from Hawaii to Harvard Law. Harris is a curveball here: Oakland ain’t fancy, Howard’s an elite HBCU, but nation-sized California’s an established kingmaker. But zoom out to culture at large and the list is endless. Minnesota-born novelist and curmudgeon Walter Kirn grumbles, fairly, that Walz is dissing a long tradition, including the great American leavers F. Scott Fitzergerald, Sinclair Lewis, and Bob Dylan just from the Land of 10,000 Lakes alone. Drag the whole American middle and the list runs deep and wide.

Because we’re on Nebraska here I’ll throw in Willa Cather, daughter of Red Cloud (pop. now only 962, an hour south of Grand Island down by the Kansas line.) Her masterpiece My Ántonia, indisputably way up there in the Great American Novel power rankings, is a Nebraska story a told by a native son who, like Cather herself, moved east to New York.

There’s a class thing here, for sure. Not that I know a damn thing about their lives, but the residents of 610 W. Divison don’t seem to be leaving anytime soon? A job in Lincoln or Omaha, maybe? Leaving takes money, and the condition of the house suggests little wiggle room.

But the flagpole pushes this further. You don’t literally plant a flag in a yard you aim to quit. Hang the flag upside down and the wall goes higher. Stop the Steal is first and foremost a symbol of fear. Those people—the Dems, the immigrants, the leavers, the neighbors—are zombies. Stay home. Pull the blinds.

This is, of course, the same verdict the meritocratic left has handed down for years. It was never entirely unfair; hard to imagine that Cather and her lifelong love Edith Lewis would have been more comfortable back in early 1900s Red Cloud.

Then here comes Walz—who as football coach sponsored his school gay-straight alliance—with a massive Greeley rewrite: Stay home, young man, and take care of the country. The redefinition can sting. “I had 24 kids in my high school class,” he bellowed in his acceptance speech, “and none of ‘em went to Yale.” Neighbors don’t leave neighbors for a goddamn Ivy, right?

But in his next breath: “Everyone belongs.” This leaver is happy to read the invitation backwards. Everyone belongs, even those of us who left. Even the long-gone expats cruising Grand Island on a summer evening in search of street cred to post on social media.

We didn’t need another photo of 610 W. Division, is the thing. We’ve got the baby pics:

We’ve got a Kodachrome slide from that trip back for Minnie’s funeral:

We’ve also got Mary’s painting.

My grandmother Mary did, in fact, become an artist. Not the East Village art monster she might’ve preferred, no, but an accomplished Sunday painter among regional circles in the Southwest. She and my grandpa met in California but settled in Tucson, AZ after the war. In 1975, her own three kids grown, she did a lovely watercolor of 610 W. Division from memory, or perhaps a photo album I’ve never seen? It’s nicely done. Took second place at that year’s Tubac Arts Festival.

It’s a curious painting, though. The perspective is actually from out front of 612 next door. The light is mid afternoon. The lines of the house are tweaked a bit; a fictional gardener trims a fictional hedge. There is no flag pole. No disturbance of any kind, really. But neither is there any note of personal connection. You can feel Nana’s interest not in her mother’s life or some larger question of roots but in the rhythm of Plains sunlight falling through 612’s imagined or perhaps long-gone white picket fence. The award certificate is still taped to the back, neatly printed with the painting’s title: “Pleasant Street.” Could be anywhere in America, really. A dream of home. Everyone belongs.

Well done!! Almost no Midwest in my family tree. My people followed different routes, different regions where they planted then uprooted themselves. And no doubt there’s some residue of anger and disappointment in those places too.

I would run thru a wall for Coach Walz - and Kamala. I too have rellies in the heartland, mainly Minnesota & North Dakota. We dont talk politics because, well, you know.

The burst of energy inspired by the change at the top of the ticket is infectuous. Haven't felt this good about the American Politic since 2008.

Thanks for sharing your family's journey, Dan. Lunch soon!