Take Me Home, Mountain Manu

That time a stag do bombed the Remutaka Hill

Halfway through the stag do we took a dip in the public pool.

That sentence feels wrong to type. A stag do—bachelor party, in the American—is a temporary man cult. Public pools are for little kids and lap-swimming grandmas.

In fact I feel wrong even writing about a stag do. The First Rule of Fight Club, and all that? But there we were, fifteen-odd dads bopping into the chlorine-stink lobby of Lower Hutt’s Huia Pool and asking for a group discount.

Oh, the face on the poor college girl behind the counter! We were filthy from paintball and already two parking-lot beers in. On my balding head was a fresh welt smeared in day-glo pink. The most charming among us pled our case. The girl blushed hard, for all of us. She called over her manager, who gave as glance and, with textbook Kiwi casualness, told the girl to just name a price.

They’re not going to be here long, the manager said.

Now this was Saturday afternoon, and the indoor Huia is immune to Wellington weather: the place was full of kids, and the kids were doing manus. Cannonballs, in the American. In New Zealand manus come in several canonical forms but the classic is the “v-bomb,” where you swing forward to land on your lower back and bum while pointing your arms and legs above in a V. I don’t understand the physics here, but done right it carves a deep hole in the water, and then, after a brief but dramatic delay, makes a huge splash.

Manus are a big deal, too. What’s a goofy backyard trick in the U.S. is here a full-fledged Māori tradition and national pastime, performed off docks and bridges in NZ’s countless bays and rivers. For an explainer see Madeleine Chapman’s definitive Spinoff essay; for vibes, dig the dearly departed rugby star Sean Wainui joyfully holding forth on the manu stylings of his fellow Chiefs. Chapman notes that manus, “the one popular, free, and brown hobby this country has,” have over the years faced racially-coded bans in some NZ public pools. Today facilities juggling schedules with (whiter, older) lane swimmers often restrict bombs to peak-kid hours—peak stag-do hours!—on weekend afternoons. If the stag do’s unwritten code permitted lining up with ten-year-olds for a turn at the diving board, our mixed Māori and Pākehā party would’ve happily bombed away. Instead we treaded water in the deep end, critiquing the kids’ techniques like the dads we were.

Anyhow the pool manager was right. We were gathered to put away childish things, and we had a table waiting at the brewery. Back outside in the parking lot, scrubbed clean in our best going-out t-shirts, we made the groom put on a chicken suit.

Can I even tell you about the chicken suit? What happens in the stag do stays in the stag do. Even here, on an entirely strip-club-free afternoon, there lives a mystery I am reluctant to approach. Or rather what I want to say would come out not in words but what a great American stag once called a barbaric yawp.

The yawp’s a-coming, I promise. But first, a theory. That mystery—the mild taboo I’m happily breaking here—is the stag do’s whole dang point. In his 2016 book The Disappearance of Rituals, the Korean-German philosopher of the moment Byung Chul Han argues that rituals—and stag and hen dos are among the few left standing atop the atomized heap of Western culture—must, by their nature, be “closed.” This closing comes in three parts: borders, collectivity, and silence.

First, rituals draw and enforce borders. At paintball we marched from one fenced enclosure to the next, reciting the rules as we went. In the sanctum ahead of us we watched, but absolutely did not call out to, another stag do in combat masks leading around their own tutu-wearing groom.

Inside those borders, Han writes, rituals represent a “collective consciousness” that does not permit individual attention-seeking. Our war games climaxed with a ceremony in which the groom sprinted past us as we emptied our clips. “Running the gauntlet,” we called it, and several of the dads had once survived their own. But we stood in a firing line precisely so that none of us could later claim that nasty stinger on the groom’s hand.

Not that anyone one even wanted to: the ritual’s bordered collective finds its truth in shared silence. Throughour his work Han loves to invoke a “community without communication.” This is a good thing, to him, like a moment of silence in church. The chicken suit just appears. At the brewery we could all tell the groom to ‘drink up, ya c***’ but, by unspoken law, the bloke who actually plunks the latest whiskey before him does so without a word.

In Han’s image, this closed, collective silence of ritual equates to—and often literally requires—a closing of the eyes. Masks are required in paintball, our young guide dryly informed us, because the guns will put your eye out. I shoved mine right over my glasses. A sweaty hour later the mask had fogged up good, and my trusty wire rims had bent their lenses in on my face just enough to make me dizzy, prompting my nerdiest tap-out since junior high. I ripped off the mask and the spell was gone.

Rituals doesn’t care about comfort. Rituals live in the dark, the separation, the fog in your mask. Rituals, Han argues, needs these blind boundaries in order to mark thresholds between ages of life:

Thresholds speak. Thresholds transform. Beyond a threshold there is what is other, what is foreign. In the absence of the imagination of a threshold, the magic of the threshold, all that is left is the hell of the same.

The emphasis is Han’s. The paintballs speak. The chicken suit transforms. Beg the pool girl for a discount and you break silence and boundary both—but no matter. Buy another round. Press on over the theshold. The hangover will feel foreign, the wedding magic. The stag do is closed precisely so that it never need happen again.

The afternoon dimmed. The breeze slipped down a couple degrees to ‘Wellington barbecue.’ Our voices got louder. Someone discovered the brewery made killer reubens and we all ordered the same. At dusk the groom’s longtime Wellington-area mates hauled our windbreaker’d chicken off to a music festival. His new Greytown neighbors aimed ourselves back over the hill.

Geography now: Wellington, NZ’s capital, wraps around a natural harbor at the southern end of the North Island. Lower Hutt, its largest suburb, fills a flat river valley on the north side of the bay. Drive up the valley and you come to the Remutaka Hill, a green, broad-shouldered peak that guards the frontier between Greater Welly and the Wairarapa, the next valley over. The groom moved over the hill to Greytown couple years ago in the work-from-home revolution. Most of us did, actually. The move crossed a well-trodden threshold of modern life, from a young man’s big-city fun to the bucolic charms of dad life. It’s rare, though, for that boundary to feature such a brutal geographic marker. The Remutaka Hill’s only 725 meters high (2380 feet), but the base starts from sea level and the peak’s got a clear shot to the South Pole. The road over it is only two lanes wide—enough to count as a national highway here—and comes crammed with hairpin turns, fathomless drops, and the odd feral goat. It’s another world up there. People die on the regular. Sometimes they close the road for wind alone. For city folks the Remutaka Hill is a bit of drama on the way to a weekend in the wineries; for us in the Wairarapa it’s a grumpy sphinx that rules our every trip to the mall, the specialist, the airport. We Greytown boys only made the stag do because one of us volunteered to be the sober driver. (We here dedicate this letter to the acolyte with a ute who stood guard just outside the beer threshold all day, so that we all might cross the mountain to get home.)

We wound up the Remutaka Hill road, fortified by the reubens but still ecstatically day-drunk. Maybe it was raining. My memory is patchy. We did not stop at the pass, with its monument to the World War I soldiers who trained on the hill before their slaughter at Gallipoli. Somewhere down the Wairarapa side we pulled over so the drinkers could pee. One does not do this on the Hill. I don’t even change the tunes on that crazy road. But it was a day for crossing lines, and forbidden places have their own magic. We stumbled out into the twilight. Just over the guardrail we found some sort of catchment pond, lined in black plastic and filled with manky highway runoff. The next step was clear. Our two boldest stripped to their shorts and jumped in. Manus in spirit, if not in form. I, too, would complete the day. I yawped. I leapt.

Now this was not a ritual, not by Han’s terms. Manus are community performance, certainly: you can’t bomb alone. The jump itself is silent, or at least wordless: Wainui knows he’s nailed a jump by the sound of the water alone. But this community without communication is not closed, in either logisitics or spirit. NZ has very few private pools. The swimming hole or city pool is a public square, the dock or diving board a soapbox. This year’s inaugural Manu World Championship held nationwide tryouts open to anyone who felt like jumping.

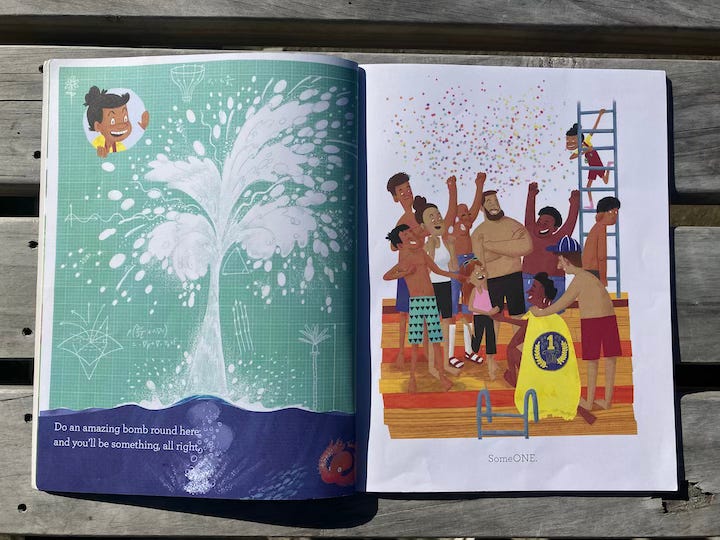

Manus also allow room for a very un-ritualistic expression of the self. In Sacha Cotter’s The Bomb, a beautiful children’s book that won all the awards here a couple years back, a young boy struggling to make his manus splash figures out the secret is to “do it [his] way.” Coached by his loving grandmother, the boy dons sequins and beads before popping a triumphant bomb in front of the gang.

But the story closes safely inside very Han-like national limits. Look closely at the lovely two-page spread of his victorious manu. Illustrator Josh Morgan infuses the towering column of spray with several Māori and NZ icons, including the koru (spiral), the tui, the extinct huia bird with its curved bill, and of course a good ol’ kiwi. In the air above the water, the book suggests, you may find your own path. But any jump is a petition for gravity to bring you home.

Or so sayeth a gringo after one drunken bomb on the Hill. From the dark of the pit I surfaced to a changed world. The summer was over now, the sky was closed. Rain and runoff streamed down my face. My boys cheered from shore. Over the guardrail cars honked as they passed, their screaming tires level with my eyes. In the failing light the green mountain scrub turned strange and alive, high above us the Hill rumbled in its misty halo, and I’d come face to face with the mystery entire.

But that’s just how it feels to lose your glasses. I had manu’d them to the bottom of the pond.

I took the loss bravely, or tried. Rituals require sacrifice! But the clarity of my baptism faded quickly. I was cold, wet, still drunk, and now blind. The sober driver later told me, not unkindly, that I looked like ‘a broken old man.’

No worries, one of the jumpers declared. He hunts, so we’ll call him the hunter.

The hunter cheerfully dove back in to the ditch. No manu now. All business. Seconds later—a jump cut, an impossible stitch in time—he sprung from the murk with my glasses in his hand. We cheered like only day-drunks can cheer.

Fucking AWESOME, I said, my best American for thank you. The hunter and I stood on the bank, dripping in our skivvies, basking in the glory of it all.

I said: I never believed we would find them.

The hunter said: I never believed we wouldn’t.

In Greytown over a nightcap jug, I tried again and again to parse the miracle. Stag do MVP! How the fuck did he find them so fast? Some duck hunter’s trick? What was wrong with me, that I could not believe?

The hunter finally set down his beer and held up a hand: silence.

The day was done. We hunters were home from the Hill. Our bruised and chicken-suited groom, even then raving in the Wellington wind with festival kids half his age, would never more a bachelor be. We finished the chips. We finished the jug. We went home to our wives.

Just a note to say I am loving this new blog series - keep writing! You have a new loyal reader in SF!

fine bomb, this!