Sioux City, IA: What if I die here?

You know you could, Jenny says, and it would be OK

A crow calls at dawn at our attic window. Down the block, a second crow calls back.

+

Morning chimes of the farmer’s market: acoustic guitar, amped gently in a parking lot. The country dude sings his covers in a striving baritone. What if die here? Who’ll be my role model, now that my role model is gone?

+

Past the music tent a mom pushes a stroller, a tactical mommy pack on her back.

+

On August 20, 1804, Sergeant Charles Floyd became the first American soldier to die west of the Mississippi. Not a bullet, not an arrow, just an undiagnosed case of appendicitis, three months into Lewis and Clark’s expedition west. He was twenty-two years old. A river here bears his name, and the wide road with a Walmart down by the train tracks.

+

Before the the Little League game we rise and remove our caps. The scorekeeper hits play on her phone. We face the right-field flag and whisper along.

+

In the museum diorama, life-size robots of Lewis and Clark stand over Floyd’s freshly dug grave. Push a button and they speak.

+

At the coffeeshop I nod to the man beside me. Will he watch my stuff a sec? He’s chewing. He’s wearing one of the red hats. He swallows and nods back: “Howdy.”

+

When you marry a rival fan, or your kids go to rival colleges, you live in a House Divided. There are flags you can buy, or just paint your own. The line is Lincoln’s, from before the War.

+

LEWIS: I keep thinking if only I’d recognized his symptoms sooner.

CLARK: It all happened so fast.

+

A baseball coach yells at a boy in the dirt. The boy rises and runs back to the dugout to cry. The coach follows in long strides, and leans into the chainlink fence to catch the boy’s eye. “I’m sorry, bud,” he says. Same as I say it to my own son.

+

There is a robot of young Floyd before his death. There is a robot of York, the slave who Lewis and Clark trusted to carry a gun. There is no Native American robot.

+

Outside the ballpark a sweaty man with a chainsaw carves a tree into a giant baseball bat. “I’m an artist,” Jason Robley says. “I don’t have a portfolio or anything. I just make things.” He got his start when a friend of his had a tree struck by lighting, and Robley carved its charred remains into a wizard. “Nine of out of ten people liked it,” he says. “But then there’s one guy who drives by and shouts ‘Merlin sucks!’” Not problem this time. “Everybody likes baseball.”

+

Dude tears round the corner on a bike. Skinny and pale, long brown hair flowing in the wind, headphones in and yelling along: “I HATE THE WAY THAT YOU WALK! I HATE THE WAY THAT YOU TALK!”

+

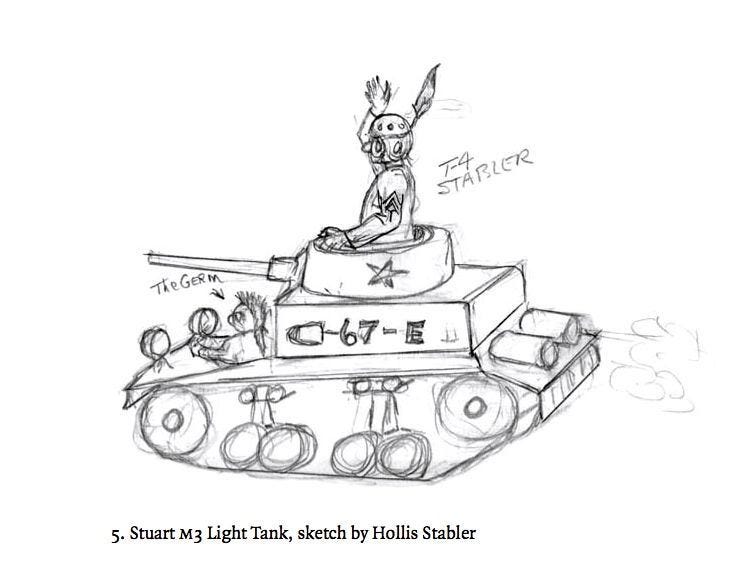

In the hall outside the diorama, a small exhibit honors Na-zhin-thia, or Slow to Rise, aka Hollis D. Stabler, an Omaha Indian who won a chestful of medals in World War II. He went home and was refused a beer in an Omaha bar. He wrote a memoir. The memoir is called “No One Ever Asked Me.”

+

My in-laws are Vikings. I am a Cowboy, or I was. I have been traveling too long. Twice they ask me if McCarthy will survive the year. Twice I confess I do not know the McCarthy of which they speak.

+

LEWIS: How are the men holding up?

CLARK: As well as can be expected. Many of them are pretty young.

LEWIS: And death a stern teacher, I know.

+

Another team, another boy thrown out trying to run home. From the dirt he looks around wildly and finds his coach back at third. The coach is a tall, broad man in a tent of a white t-shirt. He does not yell. He taps a single finger at his own heart. “That’s on me,” he says. “That’s on me.”

+

A sign by the diorama: “The captains knew that moving forward was a good antidote for discouragement. After they buried Floyd, the expedition proceeded a couple miles up the river before camping for the night.”

+

Late in the expedition, Clark fathered a child with a Nez Perce woman. The child’s name was Tzi-Kal-Tza, or Daytime Smoke.1 Lewis eventually lost his mind, likely to syphilis he caught on the trip. In 1809 he killed himself in a cheap hotel.

+

Therman Statom, a Black artist up from Omaha, speaks to a scattering of white folks at the art museum on a heat-baked afternoon. He speaks with joy about his years teaching the city’s Native American teenagers: “We are all indigenous to our own lives.”

+

In the park by the river—the Big Sioux, across town from the Floyd—a knot of white festival tents go up for this year’s Red Sky Nation MMIR Pow-Wow. MMIR stands for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Relatives. Over ten different tribes are there. There’s dancing, there’s a kickball game. You can hear the drums all the way to the public pool.

+

LEWIS: This land is something special, Clark.

+

We make a pilgrimmage to Floyd’s grave at sunset. The sand-colored obelisk glows in the golden light. Below us the interstate screams hard by the silent Missouri. By my side, my daughter is also screaming: MONUMENTS ARE BORING.

+

Past Floyd Boulevard, across the Floyd River, the trains switch and whistle through the night. Once I hear the couplers thunder as one long train yanks to a start. A steel shudder, then silence. One last whistle and the train pulls out.

Hat tip to Wild West Josh for this one!

the politics are too big. i like you on the ground

dioramas are a thing, huh?