New Zealand is a Translation

At the Hikoi to defend two very old pieces of paper

Here’s my report from the Hikoi. If you enjoy it, please share, and hit that heart button to help it move! I figure folks will disagree, too. That’s cool! I welcome all comments. I went to the Hikoi for the conversation, and I write here for the same.

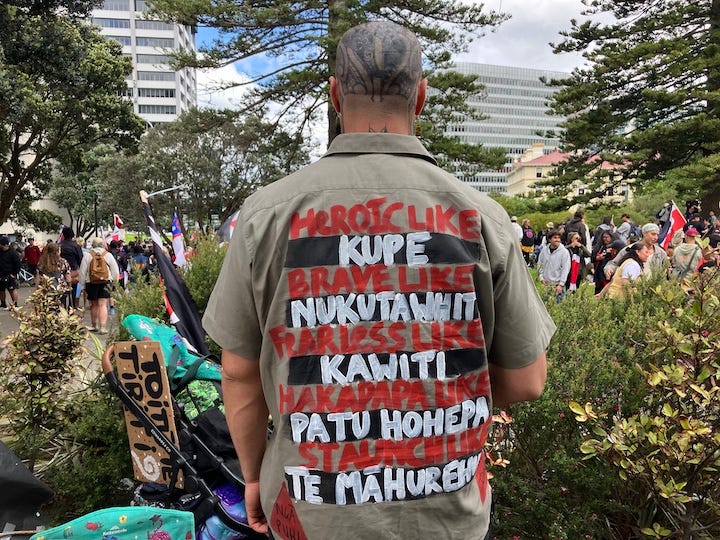

Hat tip to JR for the cover art. Just an op shop shirt, he said. Painted it himself.

So here’s a difference, maybe the difference, between our two colonial cousins: unlike the United States, New Zealand still has a living treaty with its indigenous citizens.

In the United States, of course, we broke all our treaties with the Native Americans. Every last one. Oklahoma is a broken treaty, the whole damn state. Nothing personal, Oklahoma! I got married in the Black Hills of South Dakota, on the shores of a broken treaty lake. It’s just breathing, in a settler nation like ours. We don’t look back. We don’t look down.

New Zealand has struggled with the same amnesia. For many years only British history was taught in schools here! On a long timeline, in fact, we might say the two countries have followed a very similar path: throw down an ambitious founding document, ignore it wholesale for a century or more, and then, dragged along by those left out, fitfully try to live out the true meaning of its creed.

The difference lies in the documents. Americans have a declaration, followed by a constitution. New Zealand has the Treaty of Waitangi / Te Tiriti o Waitangi, written by a British sea captain and signed by himself and forty Māori chieftains on February 6, 1840, under a tent made of ships’ sails. The Treaty has two names because it’s actually two texts, one written in English and one in te reo Māori. They’re short! Two haikus, nearly. You can read both here, alongside a handy explainer of the wiggle room between them. And that’s the difference. The United States was born by a declaration. New Zealand was born by a translation.

That translation is the national birthright 42,000 of us marched to Parliament on a windy spring Tuesday to defend. Or why I did, anyhow. My expertise here is dubious. It’s not my birthright. I’m an expat, a student-visa tauiwi who just likes to meet his neighbors and think about texts. But this was the beauty of the Hikoi: I put my feets in the streets and the We took me in. (Some cops—actual Kiwis, of course—clearly felt the same. Good on ‘em.) So let’s hear from the We, shall we?

Manukau Manukau sat on a bench on Courtenay Place—that’s him on the right—surrounded by his daughter, son-in-law, and grandchildren. He’s a retired grandfather who’d come down from Te Kuiti, up in King Country. They carried a couple large Tino Rangatiratanga flags. This was not his first rodeo:

The land belongs to Maori. It doesn’t belong to the government. We never signed over to them. We never gave away our rights to them. They’re our partners, they’re not our bloody babysitters! They’re not going to take control of us like they’ve been taking control of people around the world, this British colonization. Everywhere they want to go, they want to take things. If we went over to their land stole things from them, where would we be?

Manakau’s we here is Māori. He’s right: the British did steal a lot of things, here and elsewhere! The Treaty is maddeningly unclear on the matter of sovereignty—or rather, clear enough in its separate English and Māori texts but rather less so together. But what pops out here to me is Manukau’s use of the word babysitter. We all know that weird hierarchy from childhood. A disinterested power above, a lack of agency below, a sense that it won’t last ‘til morning.

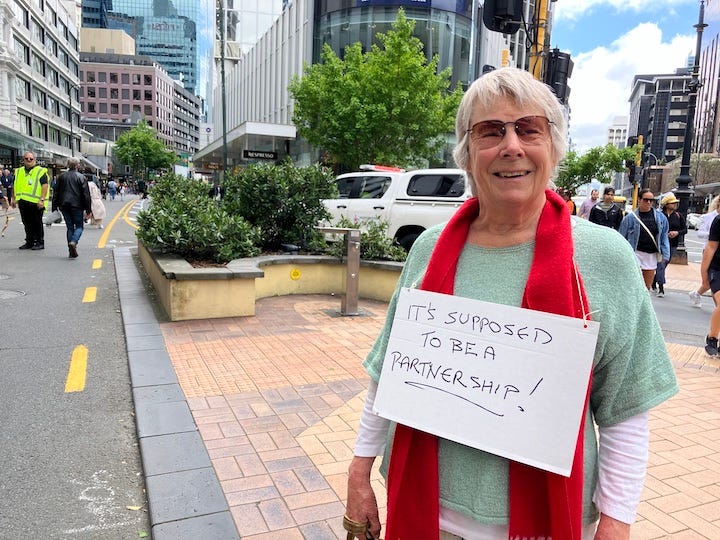

Just a ways up the street, Lee Pomeroy, 84, stood alone on the Hikoi route holding a simple handwritten sign:

The partnership means that a treaty was signed between Māori and Pākehā, between Māori and the British, that promised—what’s the word of it—promised accord, I think, between the two. And it just didn’t happen. The British took it over. It’s not an effective partnership, and it should be. Māori have been very, very badly disadvantaged in the deal…Māori were here first, Māori were here when Pākehā arrived, end of story. They have been exceedingly accommodating.

No we here, exactly. Lee, a Pākehā herself, names both parties clearly—the two parties who signed the Treaty / Te Tiriti. The Māori host accommodates a Pākehā guest. Their powers need not be equal, if that were even possible among human groups. But there is history here. Neither is a babysitter. Both will be there in the morning.

Now to the bill both Manukau and Lee were marching against. The Treaty Principles Bill was submitted to Parliament by the far-right ACT party, which won only 8.6% of the vote in last year’s general election. It has no official support from any other party, and is, for now, legislatively doomed. National needed ACT to assemble a coalition; allowing ACT to float the controversial bill was the price of the deal.1

The Treaty Principles Bill wouldn’t edit the original treaty, only fix in place a sweeping new interpretation that would restrict Māori Treaty claims to those “that hapū and iwi Māori had under the Treaty of Waitangi/te Tiriti o Waitangi at the time they signed it.” (Emphasis mine. Read the bill here.) Note the careful past tense, and the te reo words for smaller Māori political units, rather than a nationwide constituency. As a bonus, the bill would throw in recognition for any Waitangi Tribunal settlements since the original signing. But once the Treaty Principles became law—enshrined only after passing what would doubtless be a Brexit-level meatgrinder of a national referendum—that history would be over. No more claims, no more redress. Melanie Nelson explains this much better than I can. In short: NZ freezes in place, then begins again under only the third and final clause of the old Treaty, which made parties equal subjects under the Queen. If there’s a Māori language version of the bill, I can’t find it.

Forgive my American chuckle at a bill that would claim universal equality by citing royalty. I can still recognize the let’s-move-on bit. This is All Lives Matter, this is the Supreme Court tanking the Voting Rights Act because anti-Black discrimination has magically vamoosed, this is John Roberts’ famous one-liner: “The way to stop discriminating by race is to stop discriminating by race.” Catchy, no? I’ll grant ACT’s David Seymour, the Bill’s sponsor and NZ’s very own national Reply Guy, that there’s a noble but very abstract idea here, one often evoked as a way not to see either the US or NZ’s actual past and living present. And it’s not that the Treaty need never be re-read! I nod at my fellow Vic PhD Natalia Albert’s assertion that amending the Treaty might actually be healthy at some future date, it being a living document and all?

But I don’t think Seymour is interested in a living document. Check out ACT’s promo website.2 Equal rights for all, it says, right up top in ACT’s regular hot pink, over a photo of the Waitangi Treaty grounds at sunset. The photo is curiously empty. The grounds are packed every year at Waitangi Day, but here there are no living Kiwis, of any race. Just a screengrab of history, frozen in its most golden light. Who’s the We?

I keep thinking back to Matariki this year. Prime Minister Christopher Luxon, the Treaty Bill’s chief supporter-but-not, attended the midwinter ceremony on the slopes of a South Island ski resort at dawn. This is a New Zealand thing, he crowed to the TV interview. He wasn’t wrong! But surrounded by some of the country’s finest Māori singers, handsome korowhai wrapped over their monogammed puffers, the PM was weirdly careful to tiptoe around the mighty M-word.

And now this week there were 42,000 folks on the Beehive lawn, a sea of both Māori flags—the Tino Rangatiratanga and He Whakaputanga—snapping in a fresh Welly breeze.3 Not a faint signal, that. On the morning after the Hikoi, Luxon called in to RNZ for an interview with Corin Dann. The marchers came to your door, Dann said. Do you have any response?

Luxon refused to answer.

Not even pro-forma I hear you. Instead he rattled off policy outcomes for Māori like a babysitter telling the parents he’d got the kids to bed on time.

Dann asked three times: What would you say to the Hikoi? My church school ears pricked up. Surely you are one of them!

Three times, Luxon would not answer.

I’m not crazy. Nick Rockel has him doing about the same in a TV interview with Jenny May. It’s not an accident. It’s a strategy.

It’s like this: Te Tiriti is an agreement between two parties sharing the same islands. Seymour’s bill would iron it flat to the declaration of a single unified people. A constitution, of sorts. Luxon, for all his disavowals of the Treaty Principles Bill, seeks something of the same in his oft-repeated line about a “post-settlement world.”

You want NZ to have its own constitution? Let’s write one! Gather the people. Hold a convention. It’s damned hard work, writing a compromise text that will build a society and bind it together. I’ve seen this up close. As a reporter in Bolivia, another former colony with complicated settler/indigenous politics, I spent the better part of two years watching a constitutional assembly bang out a new charter. Hard yards, y’all. There were hunger strikes. There was tear gas. A riot shut the airport down.

But Seymour’s a libertarian. There’s not a state-building bone in his body. The Treaty Bill is Fast Track statecraft, a trick-shot bid to rewrite the We of a peaceful, functioning society in a few short sentences. He thinks it’s pretty clever—and it is, when you realize, as Rupert O’Brien points out in The Spinoff, that someone is going to make a lot of money once Māori can stake no more claims on New Zealand’s land, water, or any other resource you can sell.

The thing is, most Kiwis I know have no problem with the translation. Most Kiwis can imagine a nation of Māori and Pākehā and tauiwi like myself working from two slightly mismatched sheets of yellowed paper, because they live in that nation right now. It’s a pretty nice place! It’s far from perfect. But no translation ever is.

Taani Prestney brought his whole family down to the Hikoi from Taranaki. He’d already inscribed “17 November” in Sharpie on his two flags, for the Hikoi up there two days earlier. I’m sure he’s written “19 November” there now, too. He wants his four children to remember:

It’s history. When they get older, they’ll know that they’ve been here. It just means so much to being not just Māori but being a New Zealander, you know? See everyone here? That’s what it’s all about. //

Reasonable people can argue whether the deal is its own form of backhanded support, or whether that even matters. Cameron didn’t support Brexit, either.

If you squint, you can just spot the second one, aka The United Tribes of New Zealand flag or Te Kara, in that Waitangi picture on the ACT website.

Thanks, Dan, well put and a good read that sums a lot up from a tauiwi perspective...thanks for making the effort of get your thoughts out there...

Kia Ora Dan, that was an excellent read. Nice to read of the ‘why’ for some of the ‘we’.

The story regarding the Police Officers’ made me think, that while they are supposed to be apolitical, their pro- treaty assistance and behaviour would have resulted in them being MORE trusted, not less and indeed would have improved public confidence on the day. I hope their managers find the same wet bus ticket to slap them with, that National and the Speaker are using on their band of bad actors and more recently Stanford and her mean girls insult.