It's Not an Airbnb. It's a Bach.

When the internet comes for a Kiwi tradition

Welcome new subscribers! American.nz is a free weekly letter covering all things NZ/US and life in the gringo diaspora. I post on Thursdays in NZ / Wednesdays in the US. (I’ve scooted up from the old Friday schedule, because Thursday nights I’ll be at the bowls.) Some news—

Workshop. I’m hosting the The Magic of Writing it Down, a journaling workshop at Mrs. Blackwell’s Village Bookshop, on March 20 in Greytown. Come join us!

Consultations. Dreaming of a move south? Sign up for a Ask Me Anything subscription and we’ll talk one-on-one about all things NZ. More info here.

I treasure any feedback, and I’m here for the conversation—leave a comment, mash that heart button, or drop me a line anytime at dan@american.nz. On to the letter!

On our first morning at the bach a bird hit the window at dawn. We found him lying on the deck, a handsome fellow with grey wings and a high-viz yellow breast, laid out neatly beneath the glass that ended his life. The kids buried him under a rock a ways up the dirt road. On their search for a gravesite they discovered another dead bird, a baby chick of some kind, and buried that one alongside the first. Nice and tidy, one burial per child. Both eagerly shouldered the solemn weight of their task. All in all the experience improved our bach holiday, for all but the birds involved. Weird, right? ‘A bird hit the window of my Airbnb’ is a bad omen. But at the bach this felt normal, even comforting in a way I can’t explain. The difference is vague and vibey but absolutely real: We used Airbnb to rent our bach, but a bach is not an Airbnb.

So what’s a bach?

Americans: it’s pronounced batch. A modest beach house with cabin vibes. The beloved national Other, shelter-wise. They’re traditionally kept in the family but now commonly rented out, via Airbnb or NZ’s own Bookabach.1 Ours was on a working farm on the back side of Golden Bay, with a ten-minute walk to an empty beach guarded by a million wily crabs.

I’m new at this, but the place seemed dead-on for its type. Bring your own sheets and towels. Faded paua shells nailed over the deck. A double bed in the living room. A long, discursive note on the mysteries of the gas-powered refrigerator that “will keep frozen food frozen, but will not freeze food.” Instant coffee and gumboot tea. Thumbtacked photos in the kitchen: the bach in a mid-’80s rebuild, long-dead dogs playing in the surf, “Norm and Alan” on some ancient smoko in high-backed chairs. A tattered library: Barbara Pym, Steve Martini, something called We, the English, and delightful WWII flyboy pulp. Four age-slicked decks of cards mixed together in a carved wooden box. No wifi. A couple bars of moody 3G. A coal stove. A thousand-piece puzzle of cats.

Airbnb is a brand. A bach is a tradition.

Anil Dash’s Substack screed is useful here: don’t call your newsletter a Substack, and don’t call a house an Airbnb. Brands are a swirling hyperobjects of money and power that will never be yours, and a house is a built thing where your kids can sleep at night. Hard lines in language never last, though. Elevator and kleenex were once brand names, and Airbnb has long since become a common noun for any dwelling listed on the app, anywhere in the world.2

Bach, meanwhile, names a specific object in a specific country, and thus carries a specific cultural meaning. Once upon a time, bachelors in the NZ bush once built beach shacks for fishing and drinking. A postwar run of prosperity, mass immigration, and new roads cut to once unreachable beaches turned the country’s growing middle-class on to the idea, and now the bach and its associated pastimes are now top-tier Kiwiana. If your family owns one, or you know someone who does, or you can spring for the rental, that’s just where you go in summer.3 You go barefoot. You grill sausages. You fish. You drink.

An Airbnb must be frictionless. A bach must have friction.

An Airbnb comes with no such code. The word now carries a vaguely dismissive shade: No worries, we’ll just get an Airbnb, as if shelter was a canned energy drink. What began as a way to spend a night in someone else’s humble abode has made the entire world a hotel in waiting, with impossibly smooth hotel standards to meet. A tired traveler hopes for an Uber driver who doesn’t talk, and an Airbnb that is clean and unsurprising.

Our bach, meanwhile, was 25 km up a dirt road. We forgot to gas up in Takaka and spent the whole stay wondering if we’d make it out. I made spaghetti and meatballs in two batches while juggling small pans on the two propane burners. I never did get the coal stove to heat the bathwater beyond lukewarm. I took notes for this letter at the kitchen table, but I was too busy hosing off sandy kids to ever write it, and I sure as shit didn’t drive a km or so back up the road to catch a signal and post it. Airbnbs are offices in waiting, but if you’re posting from the bach, you’re not at the bach.

Airbnb is anywhere. A bach is somewhere.

David Goodhart’s two categories are maddeningly broad about people but are dead-on about rented rooms. When my mother visited us in Shanghai years ago, I installed her in an Airbnb around the corner from our apartment with a killer view of the Bund. On the wall next to the fake ferns hung a fake neon sign that said 上海 SHANGHAI, so she wouldn’t get lost. I’ve seen these in Airbnbs everywhere. Throw pillows with local slang. Texas-shaped anything. The US in particular has developed a huge market in hotel-quality map art, trinkets meant to remind us we don’t yet live in a screen.

Waiting for us at the bach was a homemade map of the farm marked with local landmarks including “chook house,” “whale skeleton,” and “Sandra’s spot” where, according to the guest book, the farm’s 80-something matriarch still skinny-dips regularly. (Per Kate Atkinson, the hand-drawn beach map is an NZ summer tradition.) The whale skeleton came with directions. We hiked through the paddocks, we stood on the flat rock, we faced the sea and took fifteen paces. At our feet lay the half-dozen blood-brown stubs of a fossilized rib cage wedged in stone just above high tide. The kids shrugged but I was transfixed. Waves boomed in the blowholes. Eons scooted by. I knelt and ran my gringo thumb over the ancient bones. I was there.

Airbnb promises the center. A bach promises the edge.

A friend of mine living in one of the oldest neighborhoods in New Orleans, one of the oldest cities in America, reports that for years now all the houses on his street are Airbnbs. Common story, this—see Barcelona, Austin, etc. Airbnb promises travelers the power to live where the coolest locals do. In many places, though, they replace a city’s beating heart with map art and rolling suitcases. This won’t stop us tourists. Like realtors we feel the hunger for location, location, location.

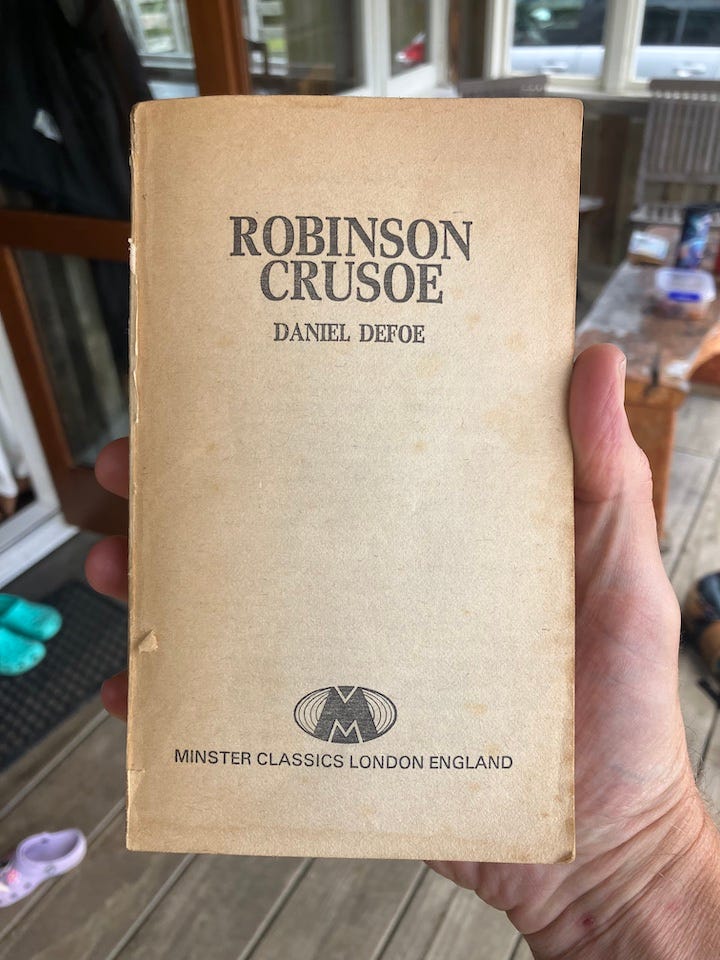

A bach’s promise, though, is the end of the world. On the bookshelf of ours I found a coverless paperback of Robinson Crusoe. The bach holy grail, really: the canonical story of a man lost at the far edge of human existence, in a book on the very edge of its own existence. I read the first few chapters, fearing every page I turned would be the last. One day, I hope, the book will crumble in a guest’s hands, and for the rest of their stay the written word will return to the murk of the sea.

The line is blurring.

The New Yorker’s Kyle Chayka noted way back in 2016 that Airbnb’s global online marketplace was driving the then-ubiquitous coffeeshop style of Edison bulbs, rough-hewn tables, and white subway tiles. He called this effect the AirSpace: if we’re all shopping the same thumbnails on Airbnb, the real-life rooms pictured in those thumbnails will all drift towards the global mean. The look has moved on—it’s jewel tones and brass fixture now—but a decade on, the force he described is only stronger.

New Zealand’s baches, then, are native trees only now turning to face the blinding sun of the internet. Over the sink at ours was a note inviting guests to join in the “Kiwi holiday home tradition” of tidying up before you leave. To use the word bach would only confuse the tourists. This is good ol’ Walter Benjamin: history is a fleeting image seized by the present the moment before it disappears. If you’re explaining the rules, the cows are already out of the barn.

Some rules have already slipped away. Our bach hosts requested, but did not require, that we pack out our trash. Kiwis do this all over—many DOC campgrounds don’t even have trash cans! But to demand Airbnbers haul their own waste is to shatter the dream. An Airbnb promises an escape from the flaming wheel of life, with a cleaning fee to cover your exit. A bach fixes you to the circle, with all its duties and limits and submission and peace.

Maybe they’re both lies. Our trash gets burnt on the farm or shipped out of Collingwood to god knows where. Crabs will feast on our ramen wrappers either way. But as we stood over the twin burial stones I knew that my family had looked life in the eye, met its challenge, and earned, however briefly, a home.

“Bye bye, bird,” my son said. “I’ve buried you in a very pretty place.” Then he turned and ran back to the house. The clouds had parted. It was time for the beach. //

Bookbach now is a subsidiary of Vrbo, which is owned by Expedia Group. The tagline still leans into the Kiwi vibes: “Relax, you’re choosing a Bookabach.”

I think of this use as simply airbnb, lowercase in spirit and perhaps one day in the dictionary as well.

Or to the holiday park, which I also adore, and deserve a love letter all its own.

I've lived here in NZ for 19 years and this feels deeply familiar and reads like home 😀🏡

I reckon you’ve nailed it Dan!!

No bach is complete without questionable cooking arrangements, an ancient book collection and a random assortment of shells and trinkets. Glad you picked a good one ☀️🌊