Been a weird week, so let’s do a weird NZ feeling I’ve never figured out. When I’m outside in the landscape here, I am often struck by the overpowering sensation that I am standing on the surface of a planet.

I mean—Earth, obviously? But the planet feeling is not so literal. It’s a vague signal, a visitation in the mind like déjà vu or that ASMR tingle. Call it planet vertigo—it’s not unpleasant, it’s even quietly ecstatic, but it’s still a wobble in the ol’ gyroscope.

The internet recently showed me a vintage photo of a Concorde in flight. See how the earth begins to curve at the edges, a sight you only see that when the sky turns black and you’re almost in space? Planet vertigo is like that. Except it’s inside your head.

I’m not a Concorde. Mornings like these I’m a dad driving his kids to school in a beat-up silver hatchback. The sun is low these days, its a pale beam through the damp. We roll up Highway 2 past the Tararuas in their winter shroud. There’s mist in the paddocks, woodsmoke in the towns. The native trees and imported pines are still green, the poplars and oaks are long bare. If it’s rained in the night the Waiohine will be up; if not, the riverbed will show its round, grey stones. I give the mountains a dad nod, my hands steady at and ten and two, and suddenly I can feel the whole Wairarapa begin to roll like a giant sphere under the tires.

Kiwis, you know what I’m talking about? Other expats here? Is planet vertigo just for outsiders, a symptom of our essential strangeness to these islands? Or do locals have their own flavor—sorry, flavour? Surely planet vertigo occurs elsewhere on Earth? (If ever had it, or if you think this is crazy, please comment below, I’d love to hear.)

I do know among tauiwi, I’m not alone. Jenny’s always felt it. As I’m writing this she dug out an old journal entry from our first New Year’s Eve in Aotearoa. We were camping in the mountains. The sky was dark and clear as outer space. The moon was upside down. Orion, too, his raised club a walking stick. We talked it about that night! she said. The planet thing!

And it’s not just us. I was on one of those Zoom readings a few years back with the writer Marco Kaye—go read him in McSweeney’s, he’s a funny guy—and when I told him I was in New Zealand, he beamed through the screen. We were on this beach, he said. The sun was going down over here, and the moon was coming up over there, and I totally felt like I was on a planet!

So that’s three. When I was reporter, we called that a trend. Let’s do this.

Marco’s italics are the key. The word itself is the pleasure: Planet vertigo.

Not Earth vertigo. Too familiar to capture the mystery. ‘I feel like I’m on Earth.’ So what.

Not world vertigo, either. The world is no more.

, the Oxford-trained philosopher turned post-humanities guru of Houston, points out that our idea of a world—in classic Western thought, anyway—was once merely a fixed background for our human lives, a holistic blank space beyond the horizon. Global warming, he says, has destroyed this idea. Nothing is fixed now, not even the seasons. No horizon is beyond our reach. That weather chitchat we perform in the checkout line of the Fresh Choice—‘more rain this weekend, they say’—no longer points to a safe, shared background but a moving, changing beast of unthinkable size and complexity. Morton calls this a hyperobject, an idea I adore—but more on hyperobjects another day.

As it turns out, New Zealand catches some interesting fire in Morton’s book. He points out that colonizers here clear-cut damn near the whole thing, replacing the native bush “a hyperbolic blowup of the English Lake District...deliberately manufactured that way.” Morton sees New Zealand’s brutal terraforming as a metaphor for the entire world dilemma. We once thought ourselves benevolent masters of a immutable universe. As that fantasy unravels, we hide away in shires:

The notion that we are living “in” a world—one that we can call Nature—no longer applies in any meaningful sense, except as nostalgia…We have a general feeling of ennui and malaise and create nostalgic visions of hobbit-like worlds to inhabit.

So is planet vertigo just Morton’s imagined world by another name? Is that why it’s a foreigner’s thing? Oh, New Zealand, you’re so cute and far away, it’s like I’m an explorer on a new planet! And isn’t planet the ultimate blank slate for cowboy adventure? Think Spaceman Spiff, think the cover of any sci-fi novel. The computer game No Man’s Sky used an algothim computer to generate 18 quintillion different planets to explore. You land on new planets, you harvest their resources, you build a cooler ship.

So I did an experiment. On a visit last year to Jenny’s family in Sioux City, Iowa, I walked from her childhood home to a park atop a nearby hill. I lay down in the grass. I turned all my radars on. Scattered evening dogwalkers. Deer shifting through the hillside scrub. Down the hill the backyards lay empty at dinnertime, and couple miles off, the wide Missouri made its southward bend. And all around me, in mystical aggregate—not a planet, but the humming bulk of a continent.

A continent is still human scale, if only just. In Fitzgerald’s famous line in The Great Gatsby, the arrival of European settlers in North America put them “face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder.” We see Fitzgerald’s colonial blinders now—‘man’ was already there, women too—but for argument’s sake this gringo’s going to run with the conversation rate: One (1) North American continent = the human capacity for wonder.

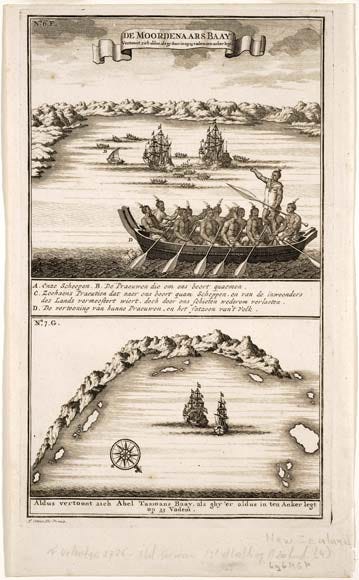

Whatever Kupe and crew felt when they rocked up at Hokianga a millenia ago, and whatever Abel Tasman felt as he scrammed out of Golden Bay in 1642 after a fatal clash with Māori waka, New Zealand is much, much smaller. Together these islands have only the land area of the very square state of Colorado—but a coastline of eleven Californias. That’s gotta count for something, right?

If an island is too small to contain human wonder, might not certain moments—a wild sunset, a misty morning drive to school—cause your human wonder to then spill out into the surrounding ocean? And once out to sea, wouldn’t that wonder run on past the horizon in search of something large enough to dream about?

This doesn’t work on any old coast. California’s every dream stands for the continent at its back. But didn’t we get hit of the vertigo on the crowded hotel beaches at Waikiki? Don’t American lubbers fly to Hawaii precisely to worship the vast Pacific, so unfathomable (to us) that it might as well be deep space? We lay out our towel. We raise a beer. We’re standing on a planet.

But there’s something in my specific New Zealand case of planet vertigo that goes beyond the metaphysical geography. There’s a budding seed of what I want to call recognition, or perhaps acceptance, buried deep in my new love of Aotearoa. Buried there, too, is my thorny ache for the real goddamn land of America. My daughter at breakfast this week: Dad, have we ever had a warm morning in New Zealand? No, we have not. It’s an island, sweetie. The winds here, like the people, always come from the sea.

And I wonder how our planet vertigo will change as we live here. Will we earn our sea legs, or will it evolve to some muted local strain? New Zealanders are not given to rapture, and do more background weather small-talk than any people I’ve ever met. They do revere their windy beaches, though, and every house, flat, holiday park, and backcountry hut is less than 75 miles from the Pacific. Those who can afford it regularly fly staggering distances over the Earth in years-long odysseys. When I’ve encountered Kiwis in farflung American airports they gave off an air of stoic patience. Planets, I think, do not make them dizzy.

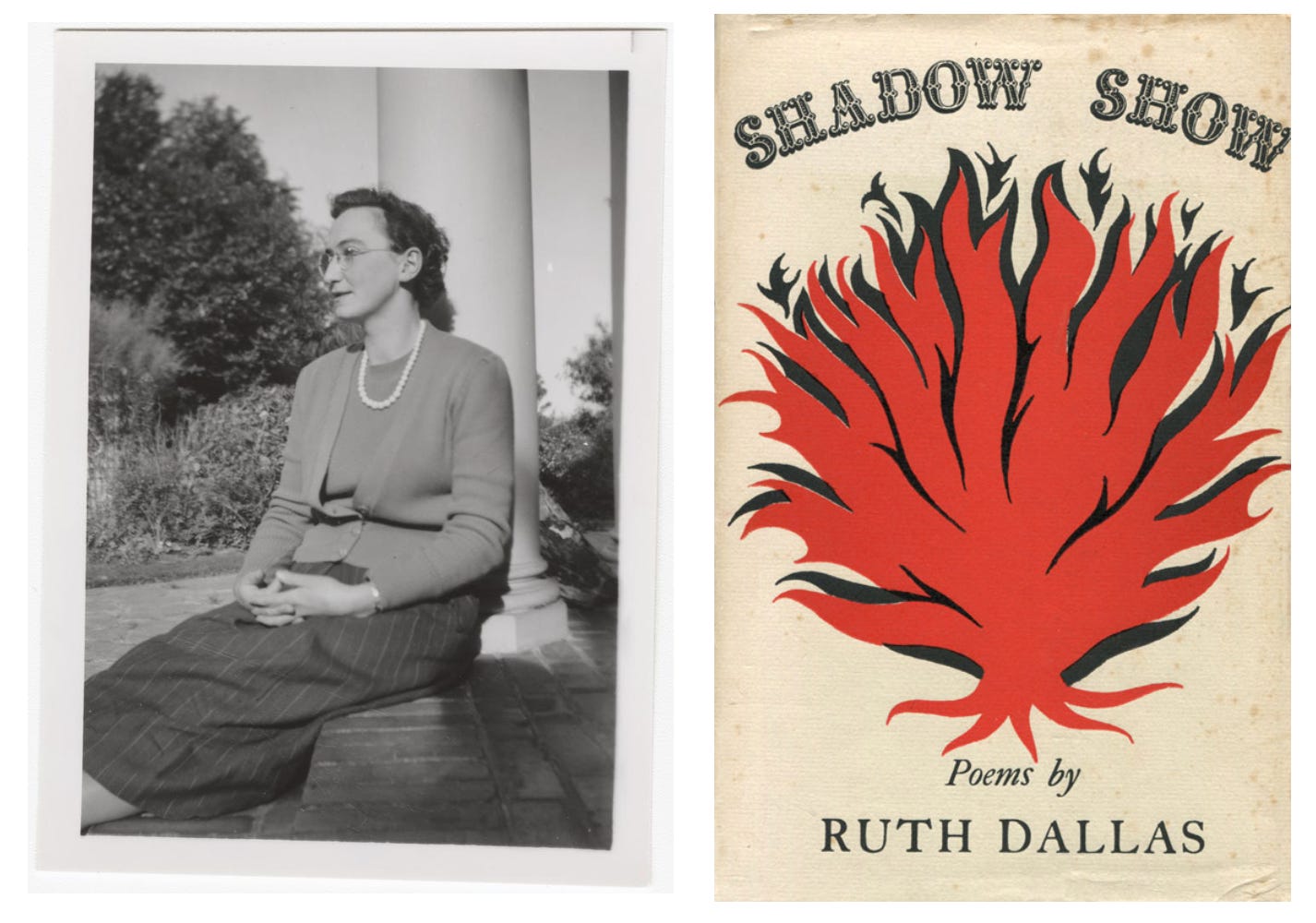

The late, great NZ poet Ruth Dallas was not such a traveler. She lived her whole life (1919-2008) in the South Island’s lower reaches, writing poems as well as New Zealand-set stories for children to replace the hand-me-down English stuff her generation had grown up on. She left the country for the first time at age 58, for a conference in Sydney; she closes her 1991 memoir Curved Horizon (!) with a fond memory following her return:

Nearer home a poem came to me after walking on the long sonorous beach between Brighton and Taieri Mouth; the boom of distant breakers sounded like gunfire and brought to mind the remembrance of war in strong contrast to the calm of the day and the immeasurable life of our planet, whose curve showed on the horizon…Like most people I had become more aware of the earth’s position in space as knowledge of the universe expanded, with the curved horizon that is visible from so many of our New Zealand beaches never failing to remind me that we are travellers in space as well as time.

All the New Zealand beaches I’ve been to, every spell of planet vertigo—these American eyes can’t see the curve. But the bard of Invercargill, y’all. She was a Concorde.

And here’s your kicker: Ruth Dallas only had one eye.

Lost one as a teenager, to a mysterious illness. By the time she wrote those lines, the other was starting to go. Her blindness gets a single page the memoir. Then she gets back to living on a planet.

Now the sun’s come out, a few last hours of daylight on the darkest day of the year. Tonight we travellers in space turn a corner, and head back into the light.

But first, I’ve got to go pick up the kids. See y’all next week—

Hey Dan, my first experience with Planet Vertigo came from laying on my back, in an El Paso public park, on hallucinogens... but I digress.

Great piece. I'm so glad Zach remembered to tell me about your substack, mucho gusto! I immediately forwarded the link to Liz, who is of course busy traveling and Not slowing down one bit, I admonished her not to skim it. ;)

I hope to see you in the not too distant future.

I read this on my way to Costa Rica -- while there, I worked to sense the "feel" of an isthmus = the Pacific on our left, the Caribbean on our right. It's an odd feeling, for sure, for us continental folks.