Dunedin’s Hanover Hall used to be a church. That much is obvious from the street. It’s a sturdy, box-and-steeple model not unlike the one in Madison, South Dakota where we baptized our kids. But Hanover Hall, see, was also a nightclub, said an indie rock dad I met at the show that night. His long, wavy grey hair took on a wizard’s halo in the pink twilight of the stained glass. “This place,” he said, “has seen all of life in its many forms.” Most of the crowd had, too. Silver wizards circled the floor. Silver angels filled the balcony pews. “Y’know,” the dad said, “I kind of feel like getting trashed tonight?” The band cranked up, we shook hands, and he headed off for another beer.

The band was Galaxie 500, or rather Dean & Britta playing the songs of Galaxie 500 alongside a much younger drummer (more on him below.) This was not, precisely, one of those classic-album tours

recently grumbled about in the NYT, but it was definitely a nostalgia trip. The famed dream-pop band split up way back in 1991. Dean Wareham, former frontman, still occasionally carries the flag; Britta, his musical and life partner for decades now, was once the singing voice of the Ameican ‘80s kids cartoon Jem.Galaxie 500 wasn’t an album band, anyway. They’re an ethos, man. A shibboleth. Growing up in Phoenix, Arizona, I never once even heard their name. I only discovered their music—was issued their music—by my hipper college classmates upon arriving Back East. So I wasn’t surprised, exactly, to spot the flyer on my first trip to the world’s southernmost college town. I was just stoked to cross paths again. Live long enough and life does these little loops.

I’d flown down for a conference at the University of Otago’s Centre for Global Migrations. We scholars of moving people gathered in the old geology building, whose narrow hallways were guarded by handsome rocks from around the world. One speaker, an American who’d brought his family along for a holiday, told the story of the soccer great Eusébio. Born in Mozambique as a subject of the wilting Portuguese Empire, Eusébio made his way to the metropole to play—proudly, by all accounts—for the Portuguese national team, most famously in the 1966 World Cup semifinal against England. When his world-class talents drew the interest of the big bad Italian clubs, Portugal’s then-dictator António de Oliveira Salazar declared Eusébio a “national treasure.” National treasures, the rule went, were not allowed to leave.

A true Galaxie 500 fan can spot the transition: Dean’s a Kiwi, the college roomie who first played them for me explained by text. I never knew. Dean had migrated, globally. The family stopped in Sydney on the way north, then young Dean hit the Dalton School, then Harvard, then played shows with early Sonic Youth. Three bright green lights at the end of the American dock, right there! And yet for a few score Gen X Kiwis, the Hanover Hall show was the homecoming of a national treasure.

“My parents took me away from New Zealand when I was very young,” Dean told us between songs, after turning down the echo box on his mic. The crowd took his cue and gently booed. “It’s OK, it’s OK.” He waved to his parents in the balcony. After 46 years in America, he said, they’d just moved back. Funny how it goes. “My dad used to tell me, ‘If you leave New York, you’re going nowhere.’” Now, in an old church on the damp edge of the civilized Earth, we were all nowhere together. The sun had finally set, and the stained glass had gone dark. Dean turned his echo back on, then sang the one about the Empire State Building on the Fourth of July.

Americans do like to let you know. The professor from Arkansas actually apologized for his American accent, bent as it was by a summer cold. My own opening humble brag is usually something like “…as you can tell by my voice.” When Dean later introduced his drummer as hailing from Phoenix—what??—I let a desperate American WOOO! sail into the vault. Nobody turned to look.

And then Dean & Britta & the Zonie played Strange. If you don’t know Galaxie 500, it’s a good place to start. Most days it’s all I need. It’s damn simple. The few words are a Frank O’Hara poem stripped even further down:

I went alone down to the drug store

I went in back and took a Coke

I stood in line, and ate my Twinkie

I stood in line, I had to wait

It’s not a cutting critique like the Stones’ Satisfaction or The Clash’s Lost in the Supermarket, its clear forebears. Dean’s narrator can almost shop happily inside the dream, though he can’t explain why. My PhD supervisor rolls his eyes at American writers who use too many brand names. But what if you’re whole country’s a brand name? It’s a great song. It’s a great American song.

And I wasn’t the only one singing along. Down the way, six bodies over, Grant Robertson knew every word.

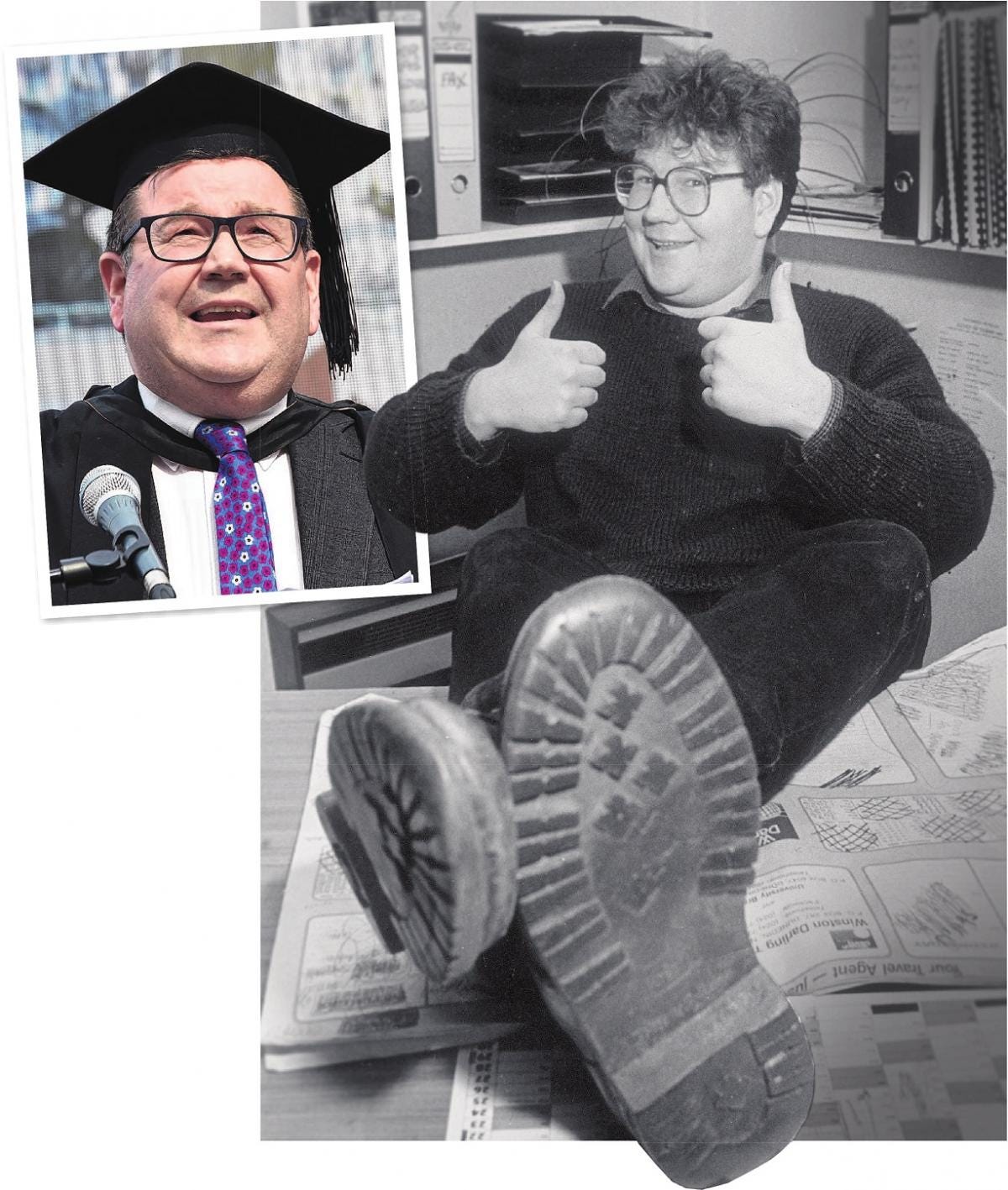

For the Americans: Grant was Jacinda’s Deputy Prime Minister, NZ’s number two through the whole pandemic. As such he was one of the handful of TV faces many of us developed strong parasocial relationships with in those years the world fell apart. Not nearly the level of Jacinda herself, or Director-General of Health Ashley Bloomfield with his soothing daily pressers. Grant was the mensch in the second row, a phlegmatic Pooh Bear in blocky glasses drolly running the budget numbers. When Jacinda quit, he could’ve run to replace her—this 2012 profile wondered if he’d one day be New Zealand’s first gay prime minister—but instead he walked away. After Labour’s 2023 wipeout he eased into a position as Otago’s Vice Chancellor, back in the town where he’d grown up and began his political career as the university’s student body president. At Hanover Hall he seemed ecstatic to be home.

The show ended and the wizards streamed out into the night. I hung around hoping to catch up with that Phoenix drummer—to say what exactly? But that was just an excuse to stand there gaping at Grant and Dean, now deep in conversation. Old friends, obviously. Then Dean’s parents came down from the balcony, the two oldest people I’ve ever seen at a rock show. (Dean’s 61, and full silver himself.) They were all so happy!

And I was happy, too. I am a bitter old goat in most things but around famous people I go all warm and stupid. I wanted to run up and clap Grant on the arm and say THANKS FOR PROTECTING MY FAMILY but then I’m not actually a Kiwi, so his shoulder’s not mine to clap? And real Kiwis, raised in this one-degree-of-separation country, would be too cool to bother a National Treasure.

That’s what he is! If you don’t like his politics: a national figure with national success. Watching him in Hanover Hall, I could nearly see the damp streets bend around him, and the cold harbour at his feet, and the green islands at his back—the whole damn nation wrapping him up like an enormous velvet cloak. Dean on the streets of New York: same. And Britta, too, whose voice I heard every day in second grade while eating Twinkies at some old lady’s house after school. Art, politics, sports, whatever: your nation is your first natural stage, your given language, the code you don’t need to switch. Most winners are too busy honing their craft inside those borders to get confused. Dean confessed this was the first time he’d taken Britta to New Zealand. Young Grant stacking veggies at the Dunedin New World didn’t dream of being a politician in Spain.

I wandered out into the street, giddy with stardust and dizzy with envy. I want to be a National Treasure, too. This switching-countries thing, man—you feel like you’ve given up your shot at the velvet cloak. That’s the rush of leaving, I suppose. To be outside the dream. Free from its failures. Free from its successes, too.

Out on the stoop I tried to get this all down in my notebook. A woman my own age cheerfully called me out. “Are you writing a review?”

I open my mouth to speak. And she could tell. //

Fab review. Nice one.

Omg. One of my fav bands. And I missed them!