I am starting this somewhere over the Pacific. The oversized plane ticks its way across the flight map’s deep computer-screen blue, and we count the hours down: NZ American is going home visiting America!

We’re trying to be very intentional with the H-word these days, to avoid confusing the kids any further. Too little, too late. My 5-year-old daughter’s been packing for weeks.

“Do we live in America, and just visit New Zealand for a long time?” she asked in the car the other day. “Or do we live in New Zealand, and just visit America for a long time?”

“This is home, sweetie,” I said, failing the first rule of politics. If you’re explaining, you’re losing.

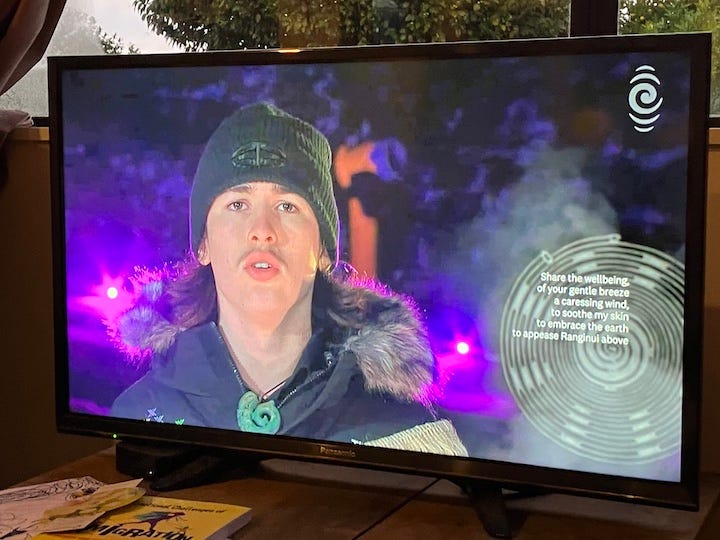

I planned to write this week about Matariki, the Māori New Year turned NZ public holiday. But that happened a week ago and I, too, have been packing since, or actively avoiding packing; in the end I just shoved some undies in a bag the morning we left. But I’m still thinking about Matariki, and it’s still midwinter in the islands behind me, so let’s do this.

If I’m explaining, I’m losing. Short version: Matariki occurs when the star cluster of the same name, elsewhere known as the Pleiades, first makes its appearance in the dawn sky. This happens near the Southern Hemisphere’s winter solstice. One of the holiday’s chief appeals, for Māori and Pākehā alike, is that it neatly covers a distinct lack of midwinter celebrations in a distant former colony whose inherited festivals all land in the wrong seasons. And now it’s a national holiday, the kind you get off from work and school.

This is crazy, when you think about it: a national holiday fixed to the stars. Matariki flies no flags, names no dead soldiers, praises no great men. In its Māori tradition, Matariki might fairly be called religious? The nine stars have names—my kids know them—and some of those names are gods. Surely I’m getting this wrong. As a secularized NZ public holiday, though, the day marks a moment when a nation, that most godlike of modern human inventions, stares up into space at an inhuman sight impossibly larger than itself.

This is weird, right? This is not what nations do. Here on the plane I ate my dinner and watched Top Gun: Maverick, in which my own native nation looks up into the sky to find itself in warplanes and Tom Cruise. Good times.

But back to the stars. We just did a Matariki night at our kids’ school. It was a lovely affair. There were tea candles in pickle jars. We ate soup and bread: a bunch of exhausted weeknight parents literally broke bread together. We lit the lanterns the kids made in art class, then we turned out the lights and the kids started to sing.

And lordy, did they sing! The songs were in Maori: more things my kids know that I haven’t learned yet. We were standing near a bunch of Year 7s and 8s, awkward preteens in their winter shorts who you’d think would rather die than sing a song at school, but these dudes were belting out every word. My daughter, too, and beaming like mad. My son stared with silent reverence at the tiny flame inside his own lantern. He gets it. This wasn’t a recital—no stage, no risers, no skits, no applause, no ‘you did so good up there sweetie!’ on the drive home. This was a ritual.

And man, it pinged this former church boy’s heart. As the kids sang I flashed back to the high holy days of my low-key suburban Episcopalian childhood. Holy Saturday, when we did our own lights-off-and-candles bit. Palm Sunday, walking a lap of the churchyard with palm fronds in our hands. The hymns, the hymns, the hymns! At some point in my smart-ass young adulthood I decided that all our joyful music unto the Lord merely slipped out through the roof and melted like lost heat into the cold black of space.

But now the same churchy joy galloped unbidden into the crowded school hall. I mean, the door was open—in New Zealand the door is often open, no matter the weather. We huddled in our jackets. Candles flickered through colored cellophane. One backup light in the ceiling wouldn’t turn off and bathed us all in its blue-milk emergency glow, making the whole scene feel strangely, and sweetly, like we had huddled together to escape a flood. I was Thursday-night tired, at home or on a visit, and suddenly damn near tears. You could almost hear the cold black space whistling by overhead. But we were not alone.

We changed planes in Denver at dinnertime on the Fourth of July. The usually mad hub was empty on America’s own near-solstice holiday. As we took off just after sunset the fireworks had started out the window. Fireworks are illegal in Colorado, so these were the public shows, the fairs, the family nights at the park. Get ‘er done early so the kids can get home to bed.

Landing in Omaha going on midnight, though—let a hundred flowers bloom. Fireworks are legal in Nebraska: you can buy a pile from a roadside stand and shoot ‘em off wherever you and yours can make a little room. We pressed our faces to the window to watch pro-grade bangers burst over suburban streets. I saw roman candles dance in parking lots, rockets leap from dark backyards. Looked just like New Years back in Shanghai, before the Party banned such displays as unbecoming of an aspiring international city. America don’t give a damn, bless its heart. In America we make—we buy, and then set fire to—our own damn stars.

Forgive me. In the airplane over your homeland, the urge to essentialize becomes something like a call to prayer. I watched the tiny fireworks below and felt—something. Not sure what. Not huddling together over a hymn. An anarchic life force, maybe. Some wild-eyed, unkillable strain popping off across a petri dish. So beautiful, and so sketch.

Which party would we be at, I wondered. Would I trust the guy lighting the bombs? Or would we stand safely in our own yard and watch the show? The explosions grew bigger as we came down from the sky. We ooh’d, we aah’d. We buckled up, and wondered when it would be quiet enough to sleep.

So lovely! The bit about the kids belting it out really got me. I have a 5 year old and 9 year old and it's such a treat going through this, particularly being part of a school with great community vibes. Loved your post -- really felt like I was there.

Aye, many thanks for this essay, Ese. Hope your whanau's visit to the Homeland is safe, enjoyable, restful and regenerative. Looking forward to catching up when you are back to Aotearoa.